By Paris Blanco

Co-Editor-in-Chief

Since its foundation in 1944, only five women have been nominated for the Golden Globes’ best director title. In 1984, Barbara Streisand, for Yentl, became the first and only woman to actually receive the award.

The same goes for the Academy Awards: in its 92 year history, only five women have been nominated for best director. Once again, in 2010, Kathryn Bigelow, for The Hurt Locker, was the first and only woman to receive this award.

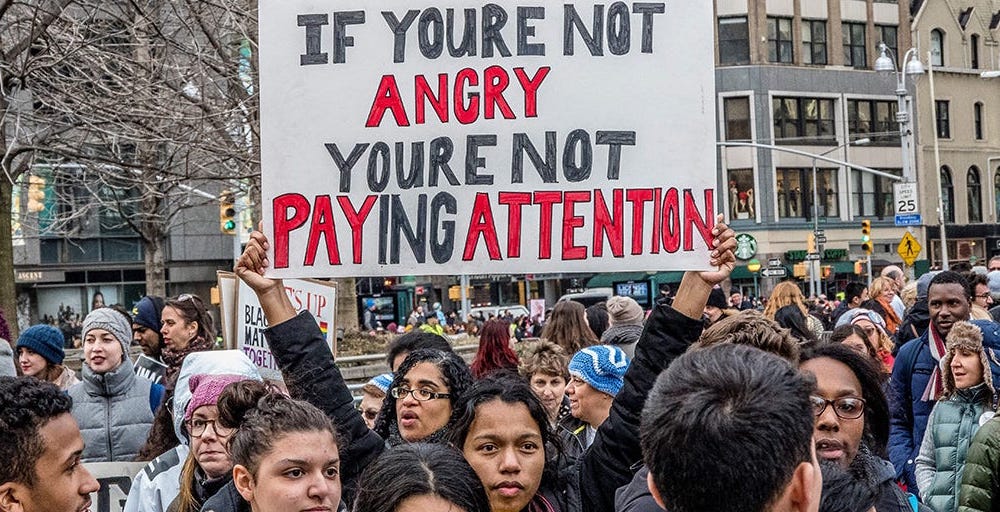

These events are not a mere coincidence. The underrepresentation of women in film (especially those behind the camera) is a problem that has plagued the film industry for much of its history.

Within the film industry, women are mistreated through the lack of opportunity created by bias. A research study published by the Sundance Institute in 2015 stated that “movies with a woman director (70.2%) were more likely than movies with a male director (56.9%) to be distributed by independent companies with fewer financial resources and lower industry clout.” On the other hand, “male-directed films (43.1%) were more likely than women-directed films (29.8%) to receive distribution from a studio specialty/mini major company.”

There is no concrete evidence pointing towards the fact that any one gender is better at creating films. The speculation that tries to prove otherwise is only fueled by bias, unconscious or not. The truth is, the equal opportunity needed to prove themselves is not given to women.

It is important that within any artform that the medium’s representation is equal. Without diverse female voices, film will never accurately depict the variety of life.

The only people suitable to write stories of women accurately are women themselves. Just like male writers are ideal when crafting stories about men, women would bring an irreplaceable perspective to stories of their own experiences.

As media becomes increasingly popular within society, it is evermore important that film accurately represents the population that it caters to. According to the Center for the Study of Women in Film and Television, “In 2016, 7% of films were directed by women (down from 9% in 2015). In other roles, women comprised 13% of writers, 17% of executive producers, 24% of producers, 17% of editors, and 5% of cinematographers.” However, this is despite the fact that women make up half of the population.

Additionally, fair and positive representation provides the population with inspiration that is relatable. Especially with children, it makes a big difference to feel properly represented through their on-screen role models.

How can we expect to constantly consume media, when the media itself does not reflect its consumers? Due to this, film turns into a one way street where the media holds a tight rein on society.

The most definitive way to solve this problem is within the industry itself, not the abilities of the people who create films. This way, excuses cannot be made for underrepresentation in film. For instance, all production companies should be required to employ at least a 50% female crew when producing films. The most plausible way for this to happen is to provide incentive or approval to companies that meet the requirements. All in all, standards and policies that promote equity and equality need to be incorporated into the film industry in order to create substantial change.

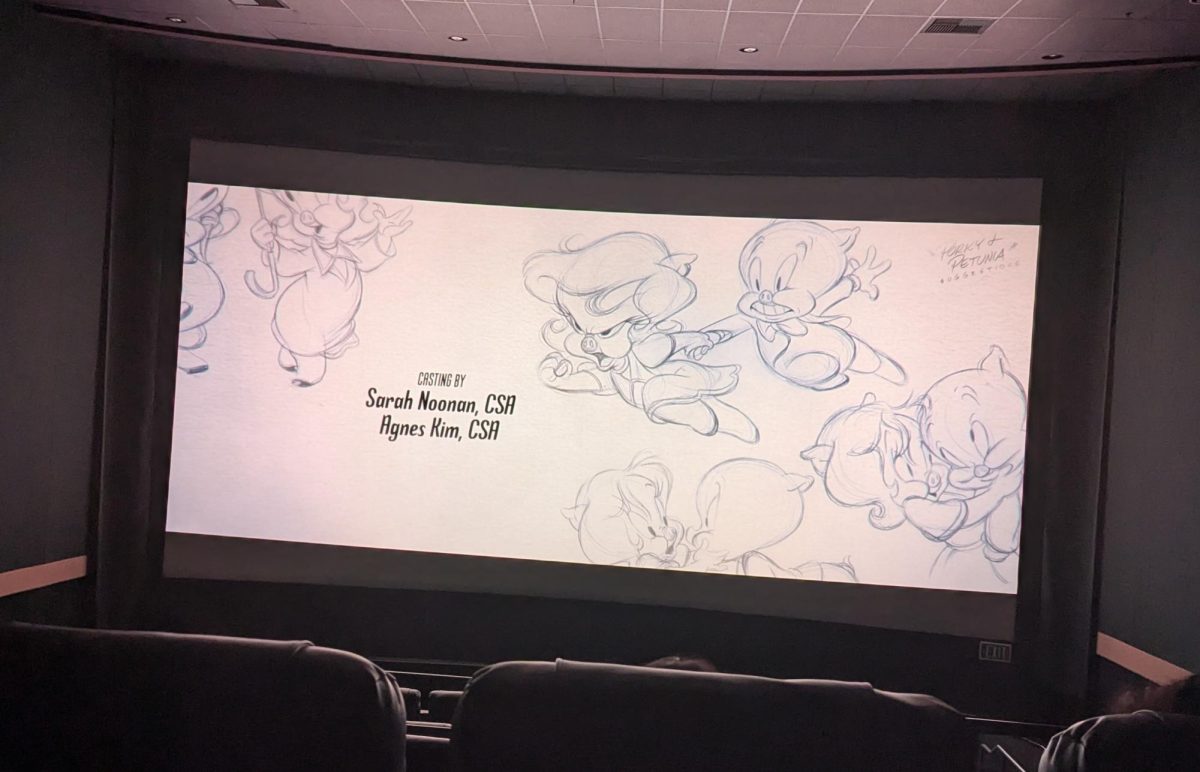

PHOTO COURTESY OF USC ANNENBERG

The bar graph above demonstrates the percentage of female film directors over the past 13 years. Although on a slight increase, the highest percentage is 10.6% in 2019.

Joseph Fausto • Mar 24, 2021 at 3:28 pm

February 3, 2021

Dear Corydon Editor,

In Issue 5 (January 27, 2021), Paris Blanco wrote an article titled “Feminism in the Film Industry.” In this article, she discusses the underrepresentation of women in film and the impact that this has had and continues to have in this industry. She makes a clear and accurate argument discussing how women face mistreatment as a result of lack of opportunities in the industry because of biased people who prefer the works of men. She goes on to elaborate how it is because of these biases, unconscious or not, are the reason women don’t even have the chance to prove themselves and their skills, hence not being given the opportunity. I enjoyed this article as it gave me a new perspective about the film industry and the unfortunate sexism that occurs within it. Even more so, this inequality between men and women in this industry is recognized by the major company the Sundance Institute and is even proven through credible sources. What more is there to say? A change needs to happen. More opportunities need to be given to women in the film industry, and that goes for all positions, including the director, the writer, and/or the editor. In doing so, this would offer a new perspective in film, and allow the audience, specifically women and young girls to feel seen through this more relatable writing and storytelling. This is very well written and I look forward to reading more works like this from Paris Blanco in the future.

Sincerely,

Joseph Fausto, Grade 11

Jonathan Lemus • Feb 9, 2021 at 1:26 pm

February 4, 2021

Dear Corydon Editor,

In Issue 5 (January 27, 2021), Paris Blanco wrote an article titled “Feminism in the film industries”. This article speaks about women not being treated equally in the film industries, they are being overlooked. They are not only being unfair with women but also they are being outnumbered by men, This just shows that women need to be given more opportunities in the movie industry. The inequality is not something new that has been going around for the past decade or more according to your chart but for the past three to four decades. I really like the fact that you provided this article with evidence and charts. It really shows that she dig deep into this topic and that she cares and has a passion for it. Me as a guy believes that women are treated very unequal in the movie industry but also out the film industry. I feel like both genders are great at acting in films but men are just giving more opportunities because of feminism in that industry. This just shows that we directors need to give more roles to women, because their acting skills are just as good as a mans. This article can force a director to think about a woman’s role in a movie. I myself did not know half of the information about the inequality in the film industry. I appreciate that you provided us with this information and some good solutions for this problem.

Sincerely,

Jonathan Lemus, Grade 12

Faith Jones • Feb 5, 2021 at 11:54 am

February 3, 2021

Dear Corydon Editor,

In Issue 5 (January 27, 2021), Paris Blanco wrote an article titled “Feminism in the Film Industry”. Right when I started to read the article a fact that I never would have known was talked about. My concern is why women are not getting the recognition they deserve. Women do so much and sometimes more than the average guy. I believe women are just as qualified as men to work in all these career fields. If women aren’t valued in the film industry no women would want to be featured as female voices and or characters. What has me so confused is, how women make up most of the population but not many are distributed into the film industry. I truly think the world needs to start supporting women in the industry because it could possibly encourage them to keep working in the film industry. The lack of support can really have an affect on them and their work. Also according to many news outlets women are mistreated, abused, sexually abused and attacked. They are paid to keep quiet or threatened so they won’t report the abuser/rapist. If they were to report the person they could be blacklisted and no one would believe them or would want to work with them ever again. This behavior needs to stop and is very unacceptable.

Sincerely,

Faith Jones, Grade 12

julia nunez • Feb 5, 2021 at 9:45 am

February 3, 2020

Dear Corydon Editor,

In Issue 5(January 27th, 2021), Paris Blanco wrote an article titled “Feminism in the Film Inudstry.” I really appreciate the writer taking the time to speak on this issue because the film industry is one that I hope to get involved with and it had never occured to me that female opportunities in the film industry was a problem. This article has brought my attention to a topic I didn’t even know about and the writer did an excellent job explaining it. Also, including the bar graph was very helpful and helped formulate the logistics of this topic. The fact that only five women have been nominated for best director was something that really surprised me and I feel that, that supports the argument very well. However, I do have some concerns on what the writer believes the solution to this issue should be. It was a bit unclear on what needs to happen in the film industry for women to get the same opportunity as men. In addition to making women 50% crew, shouldn’t there be a requirement for the studio specialty/mini major company men get, to contribute to at least a few women directed productions? Also, isn’t the problem coming from women as directors and not crew? Aside from my concerns, this Issue successfully sheds light on the woman perspective in the film industry and thank you for introducing that to me.

Sincerely,

Julia Nunez, Grade 11

Jonathan Lemus • Feb 4, 2021 at 2:28 pm

February 4, 2021

Dear Corydon Editor,

In Issue 5 (January 27, 2021), Paris Blanco wrote an article titled “Feminism in the film industries”. This article speaks about women not being treated equally in the film industries, they are being overlooked. They are not only being unfair with women but also they are being outnumbered by men, This just shows that women need to be given more opportunities in the movie industry. The inequality is not something new that has been going around for the past decade or more according to your chart but for the past three to four decades. I really like the fact that you provided this article with evidence and charts. It really shows that she digged deep into this topic and that she cares and has a passion for it. Me as a guy believes that women are treated very unequal in the movie industry but also out the film industry. I feel like both genders are great at acting in films but men are just giving more opportunities because of feminism in that industry. This just shows that we directors need to give more roles to women, because their acting skills are just as good as a mans. This article can force a director to think about a woman’s role in a movie alwell. I myself did not know half of the information about the inequality in the film industry. I appreciate that you provided us with this information and some good solutions for this problem.

Sincerely,

Jonathan Lemus, Grade 12

Londyn Phillip • Feb 4, 2021 at 12:11 pm

February 4, 2021

Dear Corydon Editor,

In Issue 5 (January 27, 2021), Paris Blanco wrote an article titled “Feminism in the Film industry”. This article was an incredibly well-written and well-informed article. I felt I learned a lot about the film industry that I had only heard rumors or claims about before. I really appreciated the inclusions of exact percentages and statistics in regards to the number of female-lead projects in the film industry. As someone who actively enjoys films and cinema, I have begun to grow more and more aware of the many underlying issues in the industry. And as someone looking to pursue a career in the industry, as a woman, these statistics really help fuel my own desire to create projects with women for women. I cannot wait to see more women in the film industry, and being recognized for their work just as the dominating men in the industry so constantly are. I also appreciated how this article included solutions to this present issue. It not only strengthened the article, but it created an interesting set of ideas that should be brought up within the film industry. If teenagers can see the issue, it’s unfathomable that such seasoned members of the industry cannot. I thought this article was incredibly insightful, and a read I won’t forget in the near future.

Sincerely,

Londyn Phillip, Grade 11

Luna Morales • Feb 4, 2021 at 10:23 am

In issue 5, on January 27th of 2021, the article “Feminism In the Film Industry” was published by Paris Blanco. This captivating and engaging article talks about how men and women are very distinct when it comes to the film industry. Statistics show percentages of female directors throughout the years which are much less compared to men. It also provides information based on how men are treated with more superiority and women have less advantage/opportunity. This is extremely unfair how women are still not equal with men and proves the point that they are more oppressed than men. However, this can change. In addition to the article talking about how men and women are treated, it also elaborates of methods they can do to fix this unjust situation. One of these methods included mandating a specific number of women to work within a producing team. By doing this it can be beneficial for women to show that they have what it takes, the ability, and the skills to produce films just like men do. With these practices and with time and patience, hopefully it will have a great impact on the industry and balance out the statistics making it more equal.

Sincerely,

Luna Morales, Grade 11

Roman Pearl • Feb 4, 2021 at 10:05 am

February 4, 2021

Dear Paris Blanco,

In Issue 5 (January 21, 2021), Paris Blanco wrote an article titled “Feminism in the Film Industry.” I think it’s very interesting how vastly under-represented women are in the film industry. I am also very concerned that the writer believes that this is not by coincidence. I don’t really believe that women are better at being film directors than men, because we really don’t have any proof of that. Conversely in the hedge-fund industry, out of the top twenty five hedge fund managers eighteen of them are Jewish. What this tells me is that Jewish people just know how to manage money more than Christians, Atheists or any other self-identifying religion. I’d also suggest for you to push the article/future articles to be non-sexually biased against men. “It is important that within any artform that the medium’s representation is equal.” This sentence most of all sparks the most concern. What are you getting at? Forced diversity in the directing industry to make it fifty-fifty because that’s what equal means. The other thing is for the writer and readers to keep in mind is we can’t just have it one way to benefit women in this industry. If we were to make everything fifty-fifty it’d ruin public elementary schools as women are vastly over-represented in that industry by a three to one ratio. Overall I think this article needs a lot of work and unbiased to be fit, and even questioning as to why men rule directing and women don’t.

Sincerely,

Roman Pearl, Grade 11

(first one had error message for me)

Emilee Renteria • Feb 3, 2021 at 11:46 pm

February 3, 2021

Dear Corydon Editor,

In Issue 5 (January 27, 2021), Paris Blanco wrote an article titled “Feminism in the Film Industry”. In this article, she depicts the ongoing underrepresentation of women in the film industry. She goes on to explain how there are very few female directors in the industry and that since 1944, there have only been five women nominated for the Golden Globes’ “Best Director’ title. Overall, this article was incredibly well written, very informative, and intriguing. For starters, the topic of the article was very unique. I myself have never come across an article focusing on the film industry, let alone the lack of representation within it. I was not even aware of the issue and getting to learn about it through this article was refreshing. I’m sure most readers will feel the same exact way if they don’t already. Additionally, I appreciated the article’s use of higher-level language and proper sourcing as they add a professional touch to the writing. Along with that, the use of rhetorical questions that require the reader to think critically, improves the article significantly. In summary, this article was excellent in every way and I enjoyed every word of it.

Sincerely,

Emilee Renteria, Grade 11

Daniel • Feb 3, 2021 at 11:11 pm

February 3, 2021

Dear Corydon Editor,

In Issue 5 (January 27, 2021), Paris Blanco wrote an article titled “Feminism in the Film Industry“. I loved how your article tackled not a well-known issue among people who consume media but a prominent one. The way you tackled counterarguments that make no sense like men are better at film and then using that to lead into why we need more female directors worked perfectly. You then proposed a solution to the problem which made it clear for the audience what should be done but the solution did have some issues. You stated that production companies should be required to hire 50% women employees but the ratio of women to men in the film industry is 1 to 4.4. This would make it extremely hard for companies to hire a 50% women staff but what could be done instead was if they were made to put more female directors behind the camera in general. There would still be an unbalance in the number of men in the film industry, but the number of women directing big-budget films would be drastically increased. Due to the number of male directors with experience behind their backs in some cases they might have to choose a female director instead of the guy with more movies under his name. Some people might respond with criticism to this how would you respond back?

Sincerely,

Daniel Zelig, Grade 11

Savanna Alba • Feb 3, 2021 at 9:37 pm

February 3, 2021

Dear Corydon Editor

In Issue 5 (January21, 2021), Paris Blanco wrote an article called “Feminism in the Film Industry”. This article basically states that ever since the year 1944, women are constantly being looked over and outnumbered by men in the film industry. I feel like society contributes to these biases that women face everyday in this industry. A lot of people’s unconscious/ conscious bias really do take over when it comes to sexism. Unfortunately this is a very well known issue that we still deal with today. This article was very informative and I feel it would be best to make this known to all students to inform them about the reality of how unfair some industries are towards women. It definitely would be a good idea to enforce only a certain amount of women within a producing team to not only increase female staff, but it would also show that women can do the same things as men do. I really enjoyed how you included concrete evidence within your article because it shows readers how real this issue is, and that it needs to be fixed as soon as possible. While reading this article I noticed you stated the problem thoroughly and gave a few solutions.

Sincerely,

Savanna Alba, Grade 12

Scott • Feb 3, 2021 at 2:32 pm

I’d suggest a policy that seeks to hire not 50% women, but instead and equal percentage or all women who apply compared to men who apply. Thus if 13% of male applicants are hired on a movie crew, then 13% of female applicants would be hired. The number of hires should depend on the number of applicants. If more of either gender want any job, then more of them will be hired. Heavy construction jobs will continue to be male dominated while elementary teaching will continue to be female dominated because of the number of applicants. But encouraging young women to work behind the cameras or any other job they desire is perfect.

Maddy Smith • Feb 3, 2021 at 12:49 pm

February 3, 2021

Dear Corydon Editor,

In Issue 5 (January 27, 2021), Paris Blanco wrote an article titled, “Feminism in the Film Industry.” I think it is a very eye-opening article that shows, with evidence, how underrepresented women are in the film industry. It is crazy that women are 50% or more of the population and yet are still not given the same opportunities as men. I respect Paris Blanco for taking a step forward in society and demanding change in such an influential industry. While the article is very well thought out, I believe that maybe it could use some more examples of female directors who created spectacular movies who didn’t receive any praise. Also, it could be beneficial to explain more ways that we can ensure that women will be given equal opportunities to receive awards for their work or even just be given the same quality resources that male directors have always been given. This article acknowledges an extremely prominent fact in society today; which is that men are constantly being chosen over women no matter the level of their skills or abilities. Paris Blanco did a great job bringing this issue to light through the example of director awards received within the Golden Globes and Academy Awards events.

Sincerely,

Maddy Smith, Grade 12

Maya Romo • Feb 3, 2021 at 10:30 am

This piece is incredibly revealing to the blatant sexism that many women in the industry face. The author does a fantastic job outlining the struggles that women, typically directors, face because of their gender. I think this article points out an important issue that many choose to ignore because it can be uncomfortable to discuss. I applaud the author’s choice to shed light on a subject that should not be controversial, but may cause backlash from those who do not feel it is a real issue. Overall, this is an important piece because it can raise awareness about the challenges women face and inspire others to make a change in the industry. The use of statistics from credible sources in the article truly makes the facts stand out. Even notable companies like the Sundance Institute acknowledge that women are given less of a chance than men at success in the director’s chair. I was surprised to find out that one of the most famous awards in the entertainment industry has only been given to one woman eleven years ago. It would be helpful to know what we, as readers, can do to spread awareness on this problem and make change. This is a wonderfully written opinion piece and I can’t wait to read more of the writer’s works. Thank you.

Elyanna Lopez • Feb 3, 2021 at 10:28 am

I had never even thought about how a conscious or unconscious bias or form of sexism could be carried over to the film industry before I read this article. It truly was a shocking but informative experience to come across this data and see the distressingly low statistics for women in the film industry compared to men, and I did find that the use of plentiful and credible statistics aided me in realizing how long this problem has been going on and how we haven’t really done much to fix it and curb the bias against women. It is a very good idea to mandate a certain amount of women within a producing team, not only to increase the female staff among movie producing crews, but also to work towards women being seen with the same level of skills as men when producing a movie. I like how you brought up the subject of accurate portrayals of gender through the producer, because it is true that if you’ve never had a first hand experience at being the gender that you’re trying to portray through a movie, it will end up not being completely accurate. This article did a very good job at thoroughly stating the problem and giving multiple ways in which we could work to fix it.

Krystal Loomis • Feb 3, 2021 at 10:23 am

To sum up this article, women have been greatly outnumbered by men in the film industry since about 1944. I believe that also contributes to many other divisions in society where women are not ranked as high as men or as not seen as an equal to men. This is a common issue today because we are still dealing with a gender wage gap, where men get paid more than women and especially gender inequality. I also think this is a great article to bring up to Millikan students because even at school we can see the unequal opportunities the men are given that the women are not. For what reason do we not have a girls football team? When creating sports, clubs and activities, it is important to think about every single person on campus. Overall this article was very interesting to read and learn about. It is something that I know a lot of students would not have taken time out of their day to research that kind of information but I’m glad it is now brought to their attention. Great article!

Violeta • Feb 3, 2021 at 8:41 am

February 3, 2021

Dear Corydon Editor,

In Issue 5, on January 27, 2021, Paris Blanco published an article on “Feminism in the Film Industry”. To start off this was a great informative article where it even demonstrated a chart showing the percentages outnumbered in the director’s chair every year. Nice job. As soon as I saw those statistics it caught my attention and wanted to learn more. I agree with what you said about how there is no concrete evidence pointing towards the fact that any gender is better at creating films and that equal opportunity is needed to prove themselves which is not given to women. Women are underestimated in the Film Industry and throughout the years we have seen more male directors receive an award or nomination for their film. Yes, the media will increase even more and it’s important for it to be diverse and show more representation in women. It will have a representation on everyone including children which will have inspiration for their role models. As a society, we need to come together and let women have a chance to be into film and hired by production companies. Women shouldn’t be stopped by anyone or judged for what their gender is but people should begin to promote equity and equality since the start of their journey.

Sincerely,

Violeta Martinez, Grade 12

Lucas • Jan 29, 2021 at 11:27 am

What I understand from reading this is that you are trying to say that women have a hard time in the film industry. in order to have a better approach to the situation I would include more of a counter argument. And what point are you trying to prove. Do you want women to have more power or equal power in the film industry. This is very important part to seeing if you have valid point or not.

Mya Delaney • Jan 29, 2021 at 10:38 am

Love this article!! 🙂